The Return of Manufacturing to the US: Fantasy or Reality?

For North America, a key concern is rebuilding the high-volume/low-cost electronic manufacturing base, from which more than 100,000 jobs have been lost to offshoring, particularly in strategic technologies and their supply chains.

All major regions involved in the electronics industry dwell on this subject – the outsourcing of manufacturing to Asia-Pacific countries. It is a key concern for a number of reasons: Currency balances, export/import trade, manufacturing infrastructures, RD&E expertise, and, of course, domestic employment.

All major regions involved in the electronics industry dwell on this subject – the outsourcing of manufacturing to Asia-Pacific countries. It is a key concern for a number of reasons: Currency balances, export/import trade, manufacturing infrastructures, RD&E expertise, and, of course, domestic employment.

For the US and the rest of North America, the main issue is rebuilding high-volume/low-cost electronic manufacturing, where more than 100,000 jobs have been lost to offshoring, particularly in strategic technologies and their supply chains. Historically, Japan and Taiwan rose to prominence on high-volume manufacturing for export, but now have seen it move to China.

Because of job loss, this subject can be compounded with feelings of protectionism by those who want to shut down foreign imports. But the issue is more about international competitiveness and a rational, effective movement to rebuild domestic manufacturing infrastructures and employment. And yes, lower trade deficits or surpluses are important, via export of products manufactured locally. In the US, the trade deficit has declined from $1 trillion, but remains stubbornly near $500 billion per year, partly due to the strong dollar. Canada is suffering from a different issue – deflation in the oil patch and failure to build the Keystone pipeline south into the US.

A stubborn US trade deficit means the US Treasury must make up its deficit through international currency transactions. Our year-to-date deficit with China in August of this year was $237 billion. Annualized, that amount would buy health insurance for 75 million people, or all of the computer industry, and equals more than 100% of domestic semiconductor industry revenues. So it is a big deal.

Recently, chatter has increased about returning manufacturing to the US. China’s labor costs are rising, and some companies want shorter supply lines and tighter quality control. Some government involvement is needed in this equation, because individual company objectives are parochial and don’t necessarily align with the US’s fiscal health. In addition, other countries do have significant government involvement. Intellectual property policies and the current disagreement with China on that subject are in the mix, as will be the next Washington administration. Government’s role is to enable the country to be globally competitive, reduce onerous regulations, and make it easier for companies to repatriate foreign earnings to invest in new manufacturing. Supporting strategic industries is a cooperative, not antagonistic, government relationship. An international trade surplus via strong exports should be near the top of the list, as should be a positive public impression of industry in general.

Recently, chatter has increased about returning manufacturing to the US. China’s labor costs are rising, and some companies want shorter supply lines and tighter quality control. Some government involvement is needed in this equation, because individual company objectives are parochial and don’t necessarily align with the US’s fiscal health. In addition, other countries do have significant government involvement. Intellectual property policies and the current disagreement with China on that subject are in the mix, as will be the next Washington administration. Government’s role is to enable the country to be globally competitive, reduce onerous regulations, and make it easier for companies to repatriate foreign earnings to invest in new manufacturing. Supporting strategic industries is a cooperative, not antagonistic, government relationship. An international trade surplus via strong exports should be near the top of the list, as should be a positive public impression of industry in general.

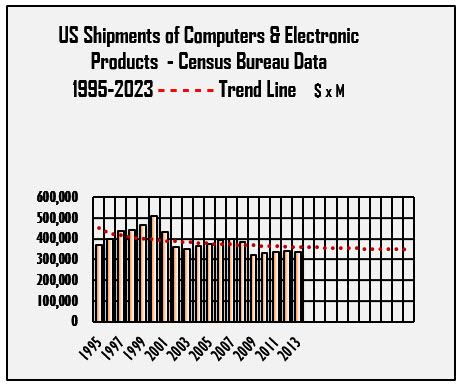

The big factors in the electronics industry are a maturation of parts of this industry, resulting in international mergers and acquisitions; faster-growing international demand versus lower domestic demand for computer and electronic products; where equipment is being assembled and supported by a local supply chain; corporate renditions to international locations with preferential tax treatment; and the macroeconomic factors mentioned above. US electronics companies have followed the business to international locations and done an exceptional job of advancing their global market. Currently, the US has improved from the seventh or eight spot in the international competitiveness index to third in the 2014-15 Competitiveness Report, but ranks 33 in best business taxes.

In the connector industry, globalization is a fact of life, particularly for top-tier multinational connector companies with revenues north of $1 billion. Scores of smaller US connector companies tend to be specialists and niche players in domestic markets with limited international exposure, but OEM customers, for the most part, no longer assemble their own products. That has gone to subcontract manufacturers, many of whom operate as a production and logistics arm of the OEM; and, of course, this does result in freeing up resources at the OEM level to develop new products.

If EMS Foxconn is assembling iPhones in China, for example, it wants its component suppliers to be close at hand. The same is true for ODMs who are specialists in PCs, notebooks, smartphones, display technology, and other products. They are mostly based in Taiwan but now assemble the end product in China for their OEM customers.

Thus, the connector and most other domestic component industries are not totally the masters of their own destinies, and domestic manufacturing for export has significant hurdles to overcome including cost structures and the strong dollar. Connecter suppliers support the OEM with design expertise, often in multiple countries, but also close the loop and sell to the CM, ODM, or EMS customer. Food chain suppliers can’t dictate where equipment is going to be assembled or where most of their parts have to be stocked and/or produced to support the contract manufacturer. Incidentally, the new Trans-Pacific Trade Pact, if ratified, could help by reducing or eliminating tariffs subject to US exports.

A major insourcing movement would have to start with OEMs dictating regional manufacture, including export of the finished product. This movement could benefit from marketing tactics or by concerns about potential work stoppages overseas. Quality and shipping costs could be a positive. Any disruption would catch much of the developed world’s supply lines off-guard – which would result in a mad rush to rebuild a domestic manufacturing infrastructure.

The best hope is for new disruptive technologies, such as the $110M AIM Silicon Photonics Program. The universe of these potential technologies and new markets is huge, spanning all manufacturing industries, not just electronics. But semiconductor technology, where the US still leads, will be a key ingredient. Supply lines would be shorter for US firms selling products here, quality and design-for-manufacturing would improve, and logistics and shipping costs would be reduced. A strong domestic economy with 4 – 5% GDP growth would help, and there is every reason to believe we can accomplish this, if the right decisions are made. Energy independence will be a key ingredient, as will be modes of transportation and healthcare.

So, given this backdrop, how do we get from here to there?

First, there are major CEOs in our industry who could promote US manufacturing from their bully pulpits. They, more than anyone, could initiate a wave of US manufacturing and get their suppliers to fall in line.

Second, the best chance for inshoring will be in new markets, technologies, and applications, plus those products best suited for manufacturing in the most developed markets in the world – the United States, Canada, and the EU:

- Chip manufacturing and its post-Moore’s-Law offshoots into SiP, PoP, and SoC

- Silicon photonics for gigabit and terabit speeds in datacom, data centers, and other Big Data applications

- The Internet of Things, which will require an amalgam of disparate technologies and communications

- The National Grid and a huge renewable energy companion infrastructure with new electrical storage technology

- Nationwide Gb/Tb Internet for a huge productivity boost

- Advanced automotive technology, including electric/autonomous vehicles and their charging infrastructure

- Automation in healthcare and medical device technology

- 4k/5K video transmission to home entertainment centers, education, and training

Thus, the viability and growth of US manufacturing is an important subject as the domestic industry moves forward as a global enterprise. Failing to improve this quadrant of our industry will have continued negative and potentially dire implications for the US economy.

We need to address this issue at all levels of management, with innovation and high-value products, closer cooperation with contract manufacturers, and with low-cost/high-volume products that can be automated. This can be done without jeopardizing our international organizations or global market penetration.

- Electric Vehicles Move into the Mainstream with New EV Battery Technologies - September 7, 2021

- The Dynamic Server Market Reflects Ongoing Innovation in Computing - June 1, 2021

- The Electronics Industry Starts to Ease Out of China - November 3, 2020