What’s Driving the Electric Vehicle Market?

First designed more than 100 years ago, electric cars are making a “comeback.” So what’s driving the electric vehicle market?

Electric vehicles were all the rage 100 years ago. They were quiet, reliable, and did not require strenuous manual cranking or shifting. They ran 35 to 50 miles between recharges, with some able to run more than 100 miles. They were heavier, slower, and more expensive than gas-powered cars. The advent of electric starters and cheap gas pretty much put them out of business – until recently.

Electric vehicles were all the rage 100 years ago. They were quiet, reliable, and did not require strenuous manual cranking or shifting. They ran 35 to 50 miles between recharges, with some able to run more than 100 miles. They were heavier, slower, and more expensive than gas-powered cars. The advent of electric starters and cheap gas pretty much put them out of business – until recently.

Due to high gas prices, a growing ecological mindset, and government incentives, electric vehicles are a hot topic once again. According to the Electric Drive Transportation Association, 487, 480 EV/HEVs were sold in the US in 2012, representing 3.38% of all domestic vehicle sales. Analysts at A.T. Kearney predict that the worldwide market for electric vehicles will soar to about $340 billion by 2020, accounting for 10 to 15% of all vehicle sales.

A.T. Kearney identifies pollution concerns, energy independence, and increasing gas prices as the main drivers of the EV market, but forward progress depends almost entirely on innovations in automotive electronics.

Step on the … gas?

When a driver steps on the accelerator in his car, he has a pretty good idea of what happens. But what about when a driver depresses the accelerator of an electric vehicle? What happens next depends on the type of EV:

- Electric vehicles (EVs – also known as Battery Electric Vehicles or BEVs), such as the Nissan Leaf, Ford Focus EV, and Tesla Model S, run entirely on electricity.

- Hybrid electric vehicles (HEVs, also known as Plug-in Electric Vehicles or PHEVs), such as the Toyota Prius and the Chevy Volt, rely on both an electric motor and gas engine for propulsion. General Motors refers to the Volt as an extended range electric vehicle (EREV) — one that runs on electricity until the battery runs down and switches over to the gas engine, if only to recharge the battery.

An electric motor exhibits maximum torque at startup, with the torque declining linearly as it speeds up. A gas engine, on the other hand, only exhibits high torque at high speed. To get a snappy response that extends to freeway speeds, some combination of the two makes sense.

There are two main HEV variants: Series hybrids like the Chevrolet Volt and power-split or series-parallel hybrids like the Toyota Prius.

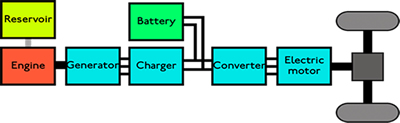

In the case of a series hybrid drive train (see Figure 1), the electric motor and gas engines operate in series. In the case of the Chevy Volt, the car runs off the motor until the battery drops below a certain level, at which point the gas engine kicks in to power a motor/generator that helps power the car. Normally, the generator just helps charge the battery bank. When the accelerator is pressed in a Volt, it supplies an increasing amount of electricity to its traction motor, which is its sole power source for the first 35 miles or so.

Figure 1: Series hybrid drive train

The Volt uses the GM Voltec powertrain, which consists of a small gas engine, a large electric motor, and a planetary gear set that couples power from the motor and, when needed, the motor/generator to the wheels. Three clutches connect the motor, motor/generator, or both to the planetary gear as needed.

With a power split or series-parallel drive train (see Figure 2), either the motor or the engine can drive the car, or if well-coordinated, both. Like the Volt, the Prius starts up in EV mode, where it stays until it achieves 25 mph or one mile, at which point it transitions to normal mode with the engine working in tandem with the motor. With the engine driving the driveshaft, the generator recharges the battery and supplies ongoing energy to the motor.

Figure 2: Series-parallel drive train

Toyota’s Hybrid Synergy Drive (HSD) system enables the Prius to run on the motor alone, except when the engine’s boost is needed. It couples both to an electronic continuously variable transmission (e-CVT) that replaces the standard gearbox. An extensive network of sensors enables the electronic control unit (ECU) to operate the system at peak efficiency regardless of speed and load.

In the case of the Volt and the Prius, the work done by the motor enables the car to function with a smaller, more fuel-efficient engine than it would otherwise need.

Electric Motoring

High-torque electric motor EVs are fast out of the chute. The Tesla Roadster can do zero to 60 mph in less than four seconds — close on the heels of the Porsche 911 Turbo GT2.

EVs rely on a variety of electric motors. The type of motor varies with the make and model of the car. For example, two variants of the Tesla Roadster use 3-phase 4-pole BLDC motors, whereas the largest variant uses a 3-phase 4-pole AC induction motor. The Volt and the Prius use a synchronous permanent magnet (PM) motor.

According to the analyst firm IDTechEx, the market for motors for EVs will reach $64 billion in 2013. Of the total market, 60% are permanent magnet synchronous motors with asynchronous AC induction motors serving in large land vehicles down to golf carts (see Figure 3). A number of manufacturers are moving to asynchronous motors in large vehicles because of their lower cost. Synchronous PM motors — the type used in on-road EVs and HEVs — win out in terms of performance, weight, and size, and since they only account for between 2 to 10% of the total vehicle price, cost is not a major issue.

Figure 3: Traction motor technology by type of vehicle (Courtesy of IDTechEx)

Driving high-torque PM motors accurately over a wide temperature range in a noisy environment is challenging. The converters shown in Figures 1 and 2 generally contain a main inverter with IGBTs or power MOSFETs to drive the electric motor; a DC/DC converter to drop the high voltage from the battery bank to 12V; and smaller inverters to drive HVAC.

Infineon FS75507N2E4 EconoPACK2 IGBT modules include six IGBTs rated at 650VCES and ICnom of 75A and ICRM of 150A. Intended for driving large PM motors, the modules are rated to 150°C and have high short-circuit capability with self-limiting short circuit current.

STMicroelectronics TD350E Advanced IGBT/MOSFET drivers are rated at 1.5A source/2.3A sink gate drive and 2 kV ESD protection. Their Miller clamp function eliminates the need for negative gate drive, and an adjustable two-level turn-off feature protects against excessive overvoltage at turn-off in case of overcurrent or short circuit conditions.

Texas Instruments’ TMS570LS Series MCUs are high-performance automotive grade microcontrollers for safety- critical applications. Based on the ARM CortexTM-R4F running at up to 160 MHz, they include three CAN controllers, a dual-channel FlexRay controller, and two UART (SCI) interfaces supporting LIN 2.0. All parts are certified for use in SIL3 automotive applications.

Give Me a Brake

What happens when the driver takes his foot off the accelerator? When the driver lifts his foot from the accelerator or presses on the brake pedal, the main drive motor temporarily operates as a generator, working to partially recharge the battery bank. In this mode, the motor produces a drag on the front wheels, which slows down the car, though not to a complete stop. As the car slows down, the effect of the regenerative braking fades out and the friction brakes take the car the rest of the way to a full stop.

General Motors measured the deceleration achieved by the Volt due to regenerative braking at 0.315g. The efficiency of the regenerative braking system was just under 75% and the efficiency of the motor as a generator in refueling the battery bank was well over 90%. As the car slows down, the efficiency drops rapidly below 0.1g, at which point the driver is increasingly reliant on the friction brakes.

Regenerative braking is a useful way to convert forward momentum back into electrical energy, extending the range of an EV. How much will it help out in practice? When the car is descending a long mountain road, it can noticeably extend the mileage and the life of the friction brakes, though just how much is hard to quantify; but for normal stop-and-go traffic, regenerative braking does not help as much.

Carrots and Sticks

The US government offers a variety of incentives for EV ownership as well as regulations that affect their design. These are the regulatory “carrots and sticks” that are major drivers of the EV/HEV industry. On the “carrot” side, the American Clean Energy and Security Act of 2009 (ACES) granted a tax credit of up to $7,500 for new qualified plug-in electric drive motor vehicles. California offers an additional incentive of $2,500 under the Clean Vehicle Rebate Project for purchasing a zero-emission vehicle (ZEV).

On the “stick” side, the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) have jointly developed a national program of standards that requires new passenger car and light-duty truck fuel economy to improve from a combined average of 27.5 miles per gallon (mpg) in 2010 to 54.5 mpg by 2025. The requirement to double fuel efficiency over the next 12 years appears to be a mandate to promote hybrid electric vehicles, and some of the largest pickup trucks are already going that route.

These are early days for modern EV and HEVs, so there are a lot of industry standards still evolving that both dictate and constrain any such designs. The major standards agencies include:

- Society of Automotive Engineers (SAE)

- American National Standards Institute (ANSI)

- Underwriters Labs (UL)

- Institute of Electrical Electronic Engineers (IEEE)

- Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI)

- Government Labs (Argonne, Oak Ridge, Pacific Northwest, etc.)

There are also a lot of standards that affect EV/HEV design (see Figure 4). Some of the standards are:

- J1772 Connector Standard

- J2931 – Electric Vehicle Service Equipment

- J2836 – General information (use cases)

- J2847 – Electronic communication between electric vehicles, utilities, charging stations, and home gateways

- J2953 – Interoperability

- IEC 62196 – Electrical connectors

- UL 2231/2251/2594 – Personnel protection systems; plugs & receptacles; EV supply equipment

If all of this sounds confusing and even overlapping, it is. The ANSI Electric Vehicles Standards Panel (EVSP) is working on a roadmap to harmonize EV standards. Doing so quickly will go a long way toward fostering EV production, thereby reducing their price and increasing adoption.

Figure 4: Electric Vehicle Standards (Courtesy of US Dept. of Energy)

Back to the Future

Electric vehicles may not be new, but they have come a long way from a switch and rheostat. They still only get about the same mileage they did a hundred years ago, however. If EVs are to really take off, they will need to become lighter, faster, and less expensive. Meeting these challenges will require a lot of engineering innovation, making the automotive industry a very attractive one for electrical engineers for years to come.

[hr]

This article originally appeared on Mouser Electronics’ website.

John Donovan is editor and publisher of low-powerdesign.com. He has 30 years experience as a technical writer, editor, and semiconductor PR representative, having survived earlier careers as a C programmer and microwave technician. John has published two books, dozens of manuals, and hundreds of articles.

John Donovan is editor and publisher of low-powerdesign.com. He has 30 years experience as a technical writer, editor, and semiconductor PR representative, having survived earlier careers as a C programmer and microwave technician. John has published two books, dozens of manuals, and hundreds of articles.