Counterfeit Components Ground Airlines

American Airlines, Delta, and Southwest Airlines are among the companies experiencing pain due to counterfeit parts entering the supply chain.

Major airlines, including American Airlines, Delta Air Lines, Southwest Airline, Virgin Australia, Ryanair, and TAP Air Portugal, have had to take more than 100 planes out of service to pursue parts removal based upon the discovery of counterfeit components obtained for servicing their CFM engines used in Boeing 737 and Airbus 370 aircraft. This problem resulted from the purchase and use of counterfeit components — including jet engine bushings — from just one firm, AOG Technics. The problem initially was flagged by TAP Air Portugal (TP) in July 2023 when it discovered fraudulent documentation for replacement parts supplied by AOG Technics. This situation shows how even the most careful ISO-certified materials departments can be fooled into obtaining counterfeit components or repair parts. The same risks exist for automotive, medical, and other critical industries where failures can have fatal results.

Use of counterfeit components is a major issue plaguing the aircraft maintenance industry, which is a growing problem as the airline industry expands both in aircraft complexity and airframe types. Fraudulent activities range from uncertified repair assemblies, work done in unauthorized facilities, to outright counterfeit parts and even potentially good parts that are expired and sold with invalid certifications to approved maintenance organizations (AMOs).

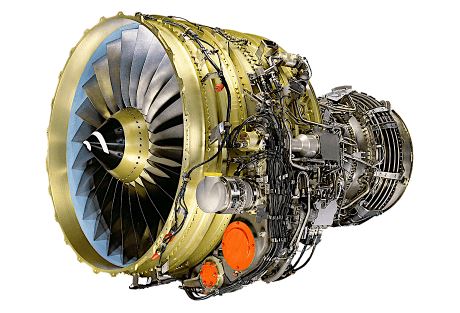

Exposed view of the CFM56 engine produced by GE and Safran Aircraft Engine Company for the popular Boeing 737 and Airbus A320 families. It is estimated that each engine has about 25,000 parts that must function perfectly over the engine’s life.

FAA says over half a billion counterfeit/unapproved parts installed each year

According to a FAA estimate, about 520,000 counterfeit components or unapproved parts currently make it into planes annually. This is about 2% of the overall 26 million parts involved with today’s flying airplanes. This may seem like a small quantity, considering that a typical commercial airplane has about 6 million components. However, we need to consider the finite tolerances for airworthiness for which each item must adhere, ranging from dimensional fit to material wear and fatigue.

Airlines, aircraft manufacturers, and even the FAA do not like to talk about these problems, as it affects public opinion about aircraft safety and flying. All of us that fly need to wonder how an intensely regulated and safety-obsessed industry could be deceived by, from-all-appearances, a virtual criminal operation. Due to increased costs and supply chain restrictions and controls, parts and report work itself often are obtained from brokers instead of from manufacturers. This represents a worldwide vulnerability that the aviation industry has been dealing with for decades, but seemingly has never successfully resolved.

A much-reported, high-profile accident involving fake parts occurred on September 8, 1989, when Partner Flight 394 carrying 55 people from Oslo to Hamburg crashed into the sea, killing everyone on board. Investigators determined that counterfeit bolts and brackets had caused the tail section of the turboprop to tear loose. Reportedly, amongst other examples, the FBI is still evaluating potentials for counterfeit parts that may have caused American Airlines flight 587, an Airbus A300-605R passenger airliner, to crash in New York on November 12, 2001.

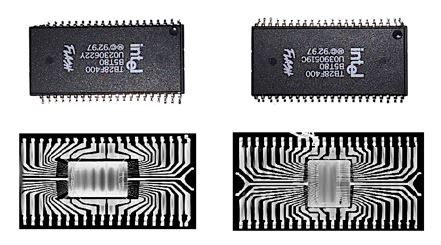

Use of counterfeit aircraft parts was heavily studied in the 1990s, with investigations by the U.S. Transportation Department’s Inspector General resulting in about 120 criminal convictions. At that time, the FAA began to proactively address this problem with its Suspected Unapproved Parts (SUP) program, reportedly prompted by the discovery of unapproved fire extinguishers, smoke detectors, and oxygen supply systems in Air Force One. The above relate to mechanical parts, but today’s studies include counterfeit chip/ICs (see example below) that have been found in everything from NASA computers to missile firing circuits and microchips located in Hercules C-130 cockpit displays.

Comparison of an Intel flash memory IC (on right) and a counterfeit (at left). Although the packaging of these ICs is almost the same, X-ray images reveal very different inside structures. (Credit: Photo by KiarashKevin86 – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia)

The U.S. Naval Air Systems Command (NAVAIR) Aging Aircraft Program estimates that as many as 15% of all the spare and replacement microchips the Pentagon buys are counterfeit. Publicly acknowledged Incidents (most are kept confidential for obvious security reasons) involving counterfeit parts include a naval destroyer that failed a training launch of a Tomahawk missile, counterfeit components installed into a communications array of Coast Guard helicopters, and the discovery of counterfeit ICs in the navigation and targeting equipment of U.S. Navy F-14 Tomcat fighter aircraft.

SAE, ISO Standards, and DFARS requirements govern counterfeiting

Part of the problem is that there are many sources, companies, and individuals involved in today’s international supply chain operations. An important industry standard is AS6171, developed by SAE International in response to the increasing volume of suspected counterfeit or tampered electronic parts, which could compromise the mission success of military weapons systems. AS6171 provides inspection and test procedures, workmanship criteria, and training necessary to detect suspected counterfeit electrical, electronic, and electromechanical parts. Other applicable SAE specifications regarding counterfeit items include AS5553 and AS6174.

Many aerospace facilities are certified to the AS9100 Quality Management System that requires organizations to take steps against counterfeit products. This includes staff awareness training; selecting and buying only from trusted sources that guarantee traceability of parts; robust inspection, testing, and verification to prevent counterfeits from entering stock; and monitoring the obsolescence of parts to make design decisions appropriate for the service life of the products involved.

Testing involves ISO/IEC 17025, which governs laboratories to operate expertly and produce accurate results to assure acceptance of their work. AS6171 and the use of ISO 17025 testing align with Defense Federal Acquisition Regulations (DFARS) 252.246-7008, which imposes responsibility on everyone in the defense electronics supply chain to carry out procedures and practices to mitigate the effects of tampered and counterfeit parts. Reportedly, the liability is such that if a component is confirmed counterfeit, everyone in the supply chain that was involved is at risk of being brought to court based upon the U.S. government’s position that everyone is responsible and must provide due diligence on parts authentication and testing.

The penalties are real. As an example, the Naval Criminal Investigative Service (NCIS), recently announced the guilty pleas of two defendants from Davie, Florida, for their participation in a procurement fraud scheme designed to defraud the US Air Force, US Navy, and the commercial aviation industry. The defendants pled guilty to conspiracy to commit airplane parts fraud, in violation of Title 18, United States Code, Section 38(a), with maximum statutory sentencing by the US. District Court up to of 10 years in prison. These convictions were the result of Operation Wingspan, a two-year investigation into the manufacture and sale of counterfeit military and commercial airplane parts, which is estimated to have involved more than $5 million and the revocation by the Federal Aviation Authority (FAA) of several FAA Repair Station Certificates for their use of counterfeit parts.

The European Union Aviation Safety Agency and Britain’s CAA are also examining reports of parts with suspected falsified documents supplied by AOG.

Consumer and MIL connectors are involved

Many connectors show up in the gray market of recycled, modified, and surplus parts. The Defense Logistics Command (DLA, part of DSCC) requires that suppliers’ assembly and manufacturing be in facilities that can be audited. Two of the largest major U.S. manufacturers of MIL-QPL connectors lost their QPL status for moving assembly to China and/or using unauthorized subcontract vendors. These are business decisions, not engineering or technology based, and illustrate how persuasive the potentials are for use of invalid, counterfeit, gray, or improperly documented connectors. This involved key connector specifications, including MIL-DTL-38999 and MIL-DTL-26482, which impacted the availability of critical parts. Connector performance and quality were not operational factors, as the connectors themselves were, as least temporarily, removed from supply chain considerations for the manufacturers and their distributors. Without QPL listing, connectors could be offered only as “designed and made in accordance with applicable MIL specifications” and could not be sold as QPL parts. Another problem, previously reported in other Bishop & Associates reports, is that counterfeit MIL-type connectors are often marketed with MIL-spec part numbers.

Did you know that MS or MIL-spec part numbers are not copyrighted or trademarked?

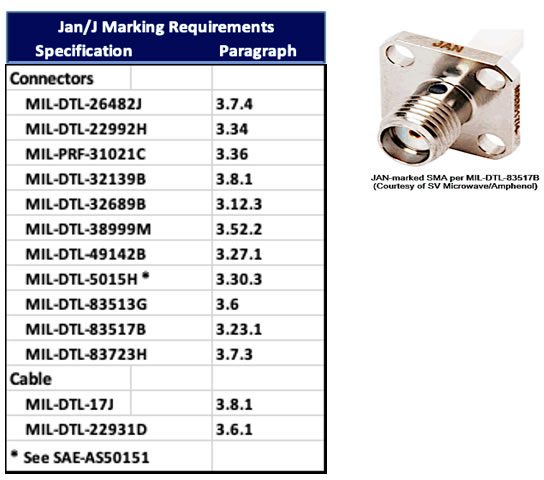

Problems with the parts themselves may result in criminal action, but unethical marking, by itself, does not represent a punishable offense. To provide an alternate path to control counterfeit items, the U.S. Government has registered certification marking of “JAN” and “J” and is adding this marking requirement to many DoD/military specifications as defined by MIL-STD-961E, paragraph 5.8.8. as follows:

“JAN and J Marking: The United States Government has adopted and is exercising legitimate control over the certification marks “JAN” and “J,” respectively, to indicate that items so marked or identified are manufactured to, and meet, all the requirements of specifications. Accordingly, items acquired to, and meeting, all the criteria specified herein and in applicable specifications, shall bear the certification mark “JAN” except that items too small to bear the certification mark “JAN” shall bear the letter “J.” The “JAN” or “J” shall be placed immediately before the part number. The United States Government has obtained Certificate of Registration Number 504,860 for the certification mark “JAN” and Registration Number 2,577,735 for the certification mark “J.”

The “JAN” or “J” is not part of the part number, but rather indicates a “certification.” Deliberately adding the JAN or J to counterfeit parts is basis for legal prosecution. Connector MIL-specs requiring the use of J/JAN marking include those in the chart below and illustrated by the connector at right.

Today’s vehicles, whether auto, truck, commercial, or military, have many standardized interconnects, including onboard diagnostic (OBD) connectors to monitor performance. The connectors are per SAE and other standards, but sourcing can be subject to counterfeiting problems. Instead of a plane crashing, improperly functioning controls in a transport truck can wipe out a section of a crowded highway.

Counterfeits, whether components such as an aircraft bolt or subassembly, a connector, or use of unauthorized suppliers such as an aircraft maintenance operator, have become a significant portion of today’s supply chain.This is a widespread and, unfortunately, not a new problem. The phrase “know your supplier” has never been more important, since parts’ failure can have life-threatening results.

David Shaff is the author of the recent report by Bishop & Associates, World Circular Market 2023.

Like this article? Check out our other Quality, Mil/Aero Market articles, and our 2023 Article Archives.

Subscribe to our weekly e-newsletters, follow us on LinkedIn, Twitter, and Facebook, and check out our eBook archives for more applicable, expert-informed connectivity content.

- New Circular Connectors Add to Multi-Billion Dollar Market - January 9, 2024

- Counterfeit Components Ground Airlines - December 12, 2023

- Cables, Connectors, Waveguides, and Hybrid Products for up to THz at IMS 2023 - July 11, 2023