Disruptive Innovation in the U.S. and China

Longtime industry observer Bob Hult shares his informed opinions, saying that it’s time for all levels of government and industry to recognize that China has become a pragmatic competitor fully capable of disruptive innovation. Doing so may help Western economies better prepare to confront the challenges ahead.

The United States has enjoyed decades of recognition as the world’s economic, technology, and military leader. Innovators including Thomas Edison, the Wright Brothers, and Henry Ford built on basic principles of others to develop ground-breaking devices that changed the world. This success has continued to build for more than a century and has created an attitude of American exceptionalism that permeates much of our thinking today. However, as financial advisors like to say, “Past performance is not a guarantee of future results.” U.S. and China

Tensions between the U.S. and China have been rising in recent years.

Recently, there has been widespread concern about the slowing rate of innovation in the United States. Many of the new devices we use today are enhancements of existing products, and few represent true game changers. Internal combustion engines still power 98% of cars on U.S. roads, and it took 40 years to replace incandescent light bulbs with light emitting diodes (LEDs). We can navigate a space probe to land on an asteroid but rely on 100-year-old clock technology to manage traffic. A basic tenet of innovative research includes the freedom to fail and learn from the experience. Pressure to meet shortened product release schedules, stockholders’ profit expectations, reluctance to change deeply embedded systems, and avoidance of risk can discourage the pursuit of leading-edge technologies.

For many years, China was perceived as a poor, agrarian nation steeped in socialism that discouraged entrepreneurship. Creative innovation was not considered to be in the country’s DNA. Its most important asset was masses of people available to work for comparatively low wages. Production of commodity products that ranged from cocktail umbrellas to personal computers shifted from the U.S. and Europe to Chinese manufacturers. Design and the technology behind new products came from the U.S., which took advantage of labor at such low costs that it more than compensated for the expense of shipping products halfway around the world.

Shenzhen has become a global hub of technological innovation, after first establishing wealth and knowledge by manufacturing technology products for Western companies. Although many of those companies have started to pull back from China, the country is maintaining its export dominance as well as serving China’s huge domestic market.

Over the past 20 years, political and social changes in China have altered this equation and the view that China is only a manufacturing center requires a paradigm shift. This drive for dominance provides plenty of incentive for them to use whatever means necessary — including predatory pricing, theft of intellectual property, and state funding — to achieve these goals. The Chinese government identified what it considers critical technologies and products that will propel the global economy in the future. To manufacture products in the volumes necessary to satisfy global demand, extensive supply chains were created throughout Asia. Consequently, China quickly became the sole source of nearly all consumer electronics. Flat-panel LCD displays were identified as another key product. As a result, China is now the top manufacturer of almost all displays used in smartphones, computer monitors, and televisions. (Foxconn promised to build a huge display manufacturing facility in Wisconsin but changed direction when the economics of using American labor did not pan out.)

Solar panels are another example of Chinese commitment to dominance in a specific product segment. Rather than rely on private corporations to recognize and fund development, the Chinese government leverages the power of its central management to direct and fund whatever is necessary to attain leadership. The Chinese government has taken a pragmatic long-term perspective in its pursuit of leadership that makes short-term losses acceptable.

At the same time, government- and corporate-funded research in the United States continues to decline. The Wall Street Journal recently reported that the U.S. now spends 0.6% of gross domestic product on federal support for R&D, down from 1.2% during the Reagan administration. Bell Laboratories, often referred to as the “idea factory,” gave birth to innovative technologies including the transistor, laser, and photovoltaic cell, but this storied American organization is now owned by Nokia, a Finnish company. Government research organizations such as DARPA still invest in military-related research, which often spills over into commercial applications, but the allocation of R&D funds by private corporations has evolved to focus more on product development rather than on basic research.

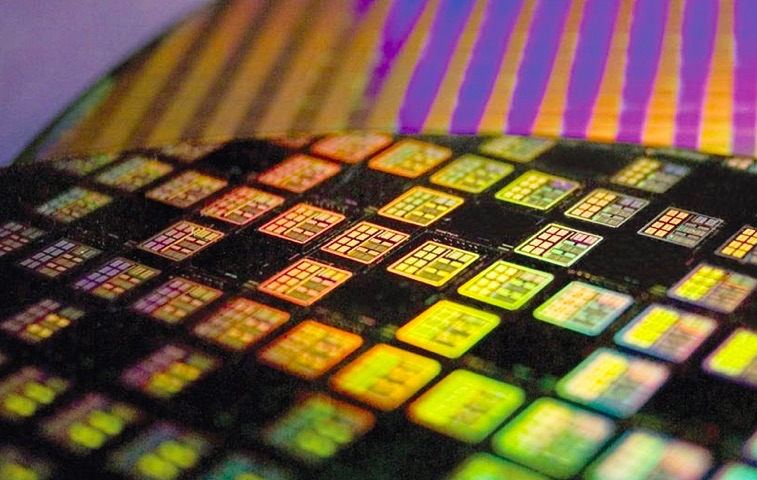

In 1965, Gordon Moore predicted that the number of transistors on a chip would double every two years and set into motion a rate of technology advances for the next 50 years. Only now are we beginning to see the physical limits of chip integration. Having led the chip industry for many years, Intel stumbled in bringing 7 nanometer (nm) chips to market at a time when Samsung and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) were shipping 7nm devices in production volumes. TSMC will soon be shipping 5nm chips to Apple for use in a variety of devices, while Intel recently sold its flash memory business to a South Korea company and is considering offshoring some of its chip manufacturing. At its current rate of growth, China is expected to become the world’s largest chip manufacturer by 2030.

TSMC’s 5nm chips will be used in Apple’s next generation of iPhones and iPads. The company invested $25 billion into the fabrication process in order to retain its sole supplier status for Apple’s A-series chips. It is now developing 3nm chips for anticipated use in 2022.

Energy is another area that represents huge opportunities and challenges as the world transitions from the burning of fossil fuels to green energy. The use of coal has been in decline for years, as it was replaced by cleaner burning, lower-cost natural gas. Now, electric cars and trucks with more affordable price tags, ever-increasing range, and significantly more charging opportunities than before threaten the deeply entrenched oil industry. Advances in nuclear energy have been on the shelf for 30 years, for a range of reasons, but are experiencing some renewed interest of late. As these and other energy technologies continue to evolve, the development of batteries with high energy density at a scale that serves industries ranging from automotive to utility will be crucial.

We are now amidst a transition in multiple technologies that will undoubtedly prove to be highly disruptive, making creative innovation essential. Concerns have already been raised about the ability of a democracy to stimulate and orchestrate the commitment to innovation in key technologies, as opposed to a top-down socialist system that has the ability to set direction unhampered by regulations, environmental concerns, and shareholder complaints.

The U.S. response to these challenges has recently focused on protection rather than innovation. The country endured many months of trade tariffs with the intent of punishing China for a laundry list of serious grievances, including government subsidies that enabled Chinese suppliers to dump goods into American markets at below cost to drive out competition. Many American companies had willingly or unintentionally transferred key intellectual property to gain access to low-cost manufacturing. Over time, that technology and expertise was honed to the point that some Asian companies are now considered world class resources, unmatched anywhere in the world.

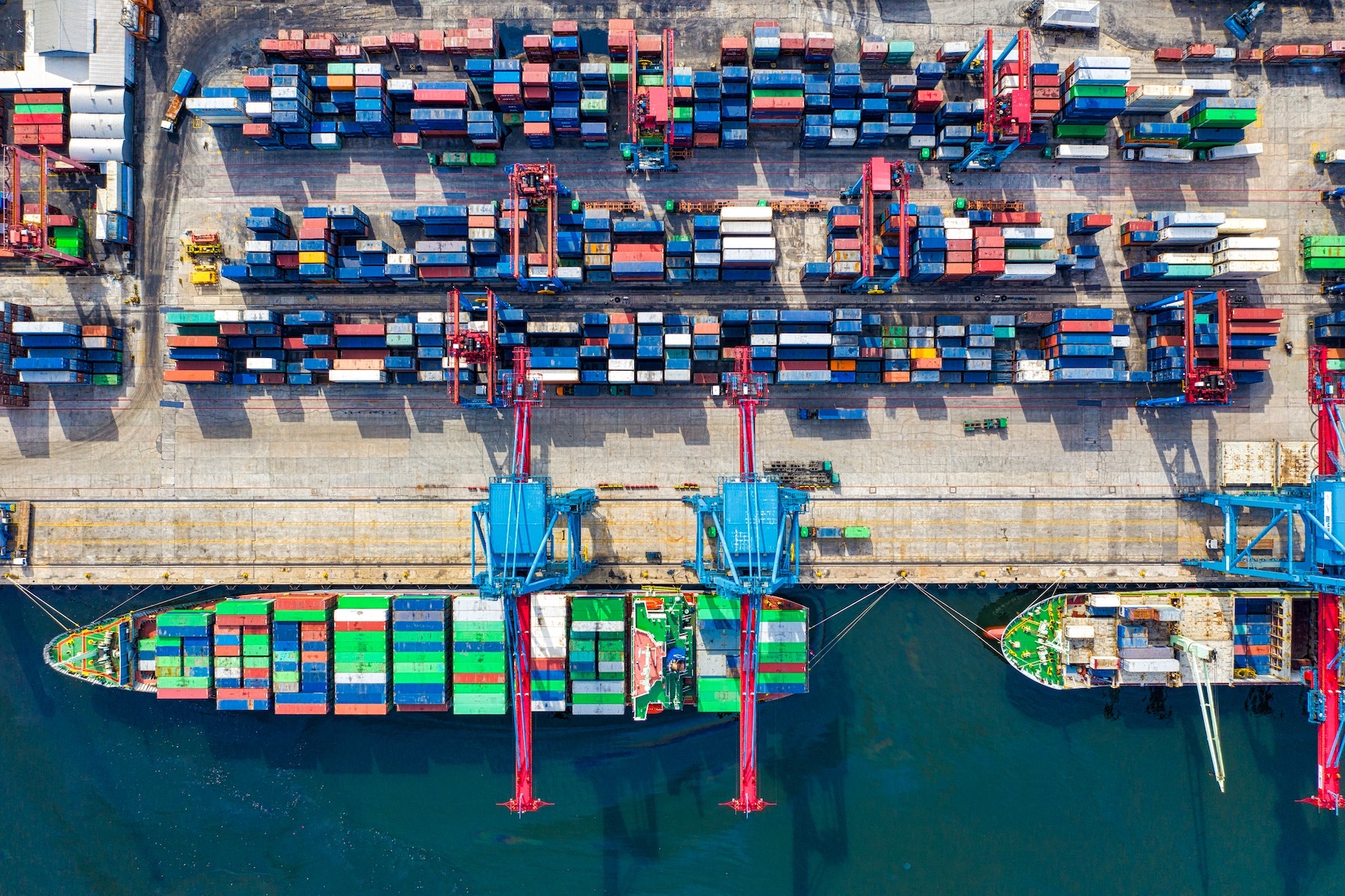

China’s exports to the U.S. in 2020 were largely unimpeded by tariffs and the global pandemic. China’s trade surplus rose to $58.44 billion in October from $42.3 billion in the same month of the preceding year.

U.S. efforts to restrict Chinese access to high-end semiconductor manufacturing equipment has spurred China to redouble its efforts to develop its own advanced semiconductor technology. The result may be the creation of a formidable competitor in this critical market. To a large degree, the imposed tariffs created only temporary hardships on Chinese suppliers and the issue protecting American intellectual property remains largely unresolved. Despite the reduction in global trade due to the pandemic and the imposition of tariffs, exports from China to the U.S. have rebounded to within 3.6% of the same period last year. Meanwhile, Chinese agreements to purchase American products are running at only about 54% of commitment through September 2020 and retaliatory tariffs imposed by China reduced American factory jobs by an estimated 0.7%. China has shifted production from supporting a global market to concentrating more on their huge domestic market. Total Chinese imports to the U.S. now total just 3% of China’s GDP. The Chinese recently approved a five-year economic blueprint that emphasizes technology self-reliance.

The U.S. would do well to take a strategic assessment of its strengths and focus them on the key determinants of future global leadership. These would include nationwide access to 5G in the millimeter bands and a commitment to emerging 6G communications, . The U.S. has already fallen far behind China in 5G deployments. Artificial intelligence is quickly becoming an enabler of advanced applications that range from factory automation to predicting personal preferences. Next-generation chip technology will shift from emphasis on higher bit rates to energy efficiency and customization for specific applications. The development of quantum computing has the potential to alter what is possible in terms of data analysis. Chinese officials have characterized dominance in these and other areas as a battle that must be won. Recognition at all levels of American government and industry that China has become a determined competitor that is fully capable of disruptive innovation may better prepare us to confront the challenges ahead.

Rather than setting up barriers to competitive manufacturers, perhaps more emphasis should be put into designing and building superior equipment, making U.S.-made products more attractive than foreign offerings. Domestic innovation incubators and accelerators — both private and those associated with a university — have proven to be highly productive sources of new technologies and products and could contribute to accelerating the pace of American innovation. Instead, we have costly plans to force mostly rural U.S. telecom suppliers to scrap their existing Huawei equipment and replace it with alternative sources, which will cost an estimated $1.8 billion and delay the expansion of 5G service. The U.S. has begun offering low-cost loans to countries for the purchase of telecom gear from suppliers other than Huawei or ZTE. An alternative would be to invest the expected billions of dollars it will cost to divert Huawei into the development of performance- and price-competitive equipment built in America instead, which would generate more jobs as well as address security concerns.

For years, many Asians came to the United States to take advantage of superior educational opportunities, and they often stayed to work for U.S. technology leaders. Today, that flow of intellectual power is being restricted as new curbs on H-1B visas are being applied. Rather than increasing American jobs, some companies have begun to shift their engineering hubs away from the U.S., the results of which have the potential to ignite an escalating cold war that wastes resources and could lead to a military confrontation that nobody wants.

There is no doubt that China represents an existential threat to America on multiple fronts. Promises by politicians to bring back massive numbers of manufacturing jobs to the U.S. ring hollow. Recreating necessary supply chains in the U.S. to manufacture commodity products would take years and would add significant cost. It is unlikely that Americans are willing to pay perhaps double or triple the prices for products such as household goods, clothing, and consumer electronics that reshoring manufacturing would require. High-volume electronic components such as connectors shifted to Asia years ago to both lower manufacturing costs and serve rapidly growing markets in that region.

This unprecedented turmoil is resulting in profound changes in the landscape of global manufacturing. Foxconn, which has relied on Chinese labor, recently announced plans to move more of its production out of China to avoid the growing conflict between the U.S. and China, as well as address concerns that the Chinese may attempt to reabsorb Taiwan. It is interesting to note that Foxconn has become one of the world’s largest consumers of robotic assembly equipment. Other companies are considering relocating out of China to avoid American tariffs. It appears that several Western nations, including the United Kingdom, Italy, and Germany, have begun countering the Chinese threat by increasing direct investment into domestic companies as an economic policy. Both U.S. political parties and industry organizations are promoting additional funding to build semiconductor factories and fund technology research. Recent events illustrate the need for U.S. domestic production of critical products such as personal protection equipment, pharmaceuticals, advanced chip manufacturing, security software, and military equipment. A well–thought–out, long-term strategic plan that positions and funds American technological innovation to confront the Chinese challenge would serve us well.

This unprecedented turmoil is resulting in profound changes in the landscape of global manufacturing. Foxconn, which has relied on Chinese labor, recently announced plans to move more of its production out of China to avoid the growing conflict between the U.S. and China, as well as address concerns that the Chinese may attempt to reabsorb Taiwan. It is interesting to note that Foxconn has become one of the world’s largest consumers of robotic assembly equipment. Other companies are considering relocating out of China to avoid American tariffs. It appears that several Western nations, including the United Kingdom, Italy, and Germany, have begun countering the Chinese threat by increasing direct investment into domestic companies as an economic policy. Both U.S. political parties and industry organizations are promoting additional funding to build semiconductor factories and fund technology research. Recent events illustrate the need for U.S. domestic production of critical products such as personal protection equipment, pharmaceuticals, advanced chip manufacturing, security software, and military equipment. A well–thought–out, long-term strategic plan that positions and funds American technological innovation to confront the Chinese challenge would serve us well.

Like this article? Check out our other Facts & Figures, China, Manufacturing, 5G, and Alternative Energy articles, our Industrial, Consumer Electronics, and Datacom/Telecom Market Pages, and our 2020 and 2019 Article Archives.

- Optics Outpace Copper at OFC 2024 - April 16, 2024

- Digital Lighting Enhances your Theatrical Experience - March 5, 2024

- DesignCon 2024 in Review - February 13, 2024